Final Report

Summary

We parallelized closeness centrality calculation for weighted graphs and applied the algorithm to graphs that we mined via Facebook Graph API. We developed several implementations using OpenMP, MPI, and achieved 15x speedup compared to a C++ boost implementation. We also implemented a mining script that allows us to apply the algorithm to real Facebook data.

Backround

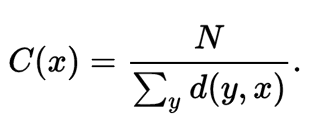

Closeness centrality is a metric expresses the average social distance from each individual to every other individual in the network. To calculate it, we divide 1 by the average shortest path from an individual to all other individuals in the network. Closeness centrality tends to give high scores to individuals who are near the center of local clusters in an overall larger network. High closeness centrality individuals tend to be important influencers within their local network community.

Problem setup. We wanted to apply closeness centrality to social graphs, and present the results by outputting a table with vertices (individuals) and their closeness centrality scores. As a constraint we decided to work with weighted graphs only. This eliminated the option for using BFS.

The most computationally expensive part of closeness centrality calculation is getting all pairs shortest paths (APSP). The 2 main conventional approaches for that are Floyd-Warshall algorithm and Dijkstra’s. Floyd-Warshall operates on adjacency matrix and returns a matrix with APSP distances. Dijkstra’s is for single source shortest path, so it’d need to be repeated for each vertex. Despite this, sequential Dijkstra’s is faster for sparse graphs: complexity is O(V^2*logV) [V*logV repeated V times], while Floyd-Warshall’s is O(V^3). Social network graphs are sparse, so sequential Dijkstra’s is faster than Floyd-Warshall for our use case.

The 2 parallelization technologies we focused on were OpenMP and MPI. Baseline we compared against was C++ boost implementation.

Finally, we applied closeness centrality computation to real Facebook graphs. We used a Python API which has a function to provide connections for a given user. The graph had to be weighted, so we added a metric to assign weights to friendships.

Approach

We analyzed 4 combinations of 2 algorithms(FW and Dijkstra’s) and 2 technologies (OpenMP and MPI).

Floyd-Warshall + OpenMP.

While working with OpemMP we figured that iterations of the outermost for loop in the algorithm were not independent, so not much speed up could be achieved. Inner loops were parallel, but OpenMP’s overhead for launching a gang of workers would be repeated for each iteration of the outermost loop and the implementation would only got slower.

Floyd-Warshall + MPI. The first algorithm that we implemented was one that just divides the matrix into horizontal blocks with each process taking care of certain rows in the matrix and communicating the results to other processes and finally the master gathering the result.

We also analyzed the performance of a technique similar to the fox algorithm for matrix multiplication in which we divide the whole distance matrix into equal sized square chunks and assign them to each of the processes (reference code). In this approach, each process keeps two arrays containing information about the row and column indexes of the elements which the process owns and are needed by the other processes. These arrays determine the data that’s communicated between processors. After exchanging the data, processes calculate new values for their part of the distance matrix and send the updated value to the master process which then gathers all the small result matrices and populates the final result matrix.

Dijkstra’s + OpenMP. As mentioned before, the end result we needed was closeness centrality scores for all individuals, so we needed shortest path distances for each vertex in a graph. Therefore, we applied OpenMP to run the searches in parallel with each other. Unlike Floyd-Warshall, there is a lot of implementation details left out in the algorithm pseudocode.

We went through a couple iterations of speeding up sequential Dijkstra’s. We started with the implementation from GeeksforGeeks. For fast extract-min, it uses C++ standard library’s priority queue. The priority queue, however, doesn’t provide decrease-key function (part of relax in pseudocode). The online implementation deals with it by inserting the vertex in the priority queue again. This adds overhead in the end of the computation. We optimized the online implementation by adding a finalized array and tweaking the data scope (e.g. got rid of OOP).

Dijkstra’s + MPI. MPI is more suitable when threads are working together on solving one problem. In Dijkstra’s, that would mean parallelizing each individual search. One spot to parallelize could be when the next closest node is selected among neighbors. However, for a sparse graph, there are not that many neighbors and so MPI would just slow us down with communication overhead. Besides, the number of vertices in our graphs was larger than the number of cores, so parallelizing Dijkstra’s within would only be relevant for single source search applications.

For mining, the challenges were working with Facebook graph structure and weighing the edges. The mining basically consists of the following steps:

- We initially don’t know the size of the graph, so store data in adjacency list.

- Explanation for next step: For weighing the edges, we decided to use the number of mutual friends as a metric.

- Make an adjacency matrix and move the graph data.

- Convert adjacency matrix to distance matrix by counting mutual friends and giving a normalized distance from 0 to 1.

- Store the graph in text file by listing all edges. One compication we ran into was the fact that it’s not possible to see connections of friends’ friends’ due to Facebook privacy restrictions. So most of the graph is represented like directed but at the edges (sides) of the network, the graph ends up being represented as undirected. So it’s not possible to mine further than depth=2 with Facebook API. Graphs we are able to get contain around 1000 vertices, so we left them for the application part, not speedup testing.

Results

Floyd-Warshall + MPI. We ran the algorithm over graphs varying in sizes (shown in the table below) we got reasonable results for relatively smaller graphs but once we tried running it on much larger graphs (of the order of 40K nodes and above) the algorithm proved out to be prohibitively slow. We suspect that the reason is that although the algorithm does involve divide and conquer approach but the number of nodes that each process needs to handle is still very high and MPI introduces a lot of communication overhead as well. The memory footprint of this algorithm is also very high since we need to have temporary arrays at each node as well.

Dijkstra’s + OpenMP. Our sequential Dijkstra’s was slightly faster than C++ boost library function. We proceeded with boost implementation as the baseline, as it’s considered high quality and is commonly used.

We tested the parallel implementation against the sequential boost by running closeness centrality on a weighted connected social graph. We used Twitter graph from Konect. This graph comes unweighted in size too large for sequential version, so we did some processing in Python: added random weights to edges and cut down the graph to 40K vertices. The graph is represented as a text file with 3 values per line (src, dst, weight), for each edge.

Below is the plot showing the speedup of centrality calculation with parallel OpenMP Dijkstra’s. The speedup is calculated using formula sequential-boost-runtime/parallel-runtime.

We ran this test on linux.andrew.cmu.edu machine which has 2 6-core hyperthreaded Intel Xeon Processor E5645 cores, totaling in 24 threads. This explains why our speedup plot goes flat after 24 cores.

We speculate that the speedup is not linear because it’s bandwidth bound. Each thread keeps a priority queue, a finalized vector, and centrality scores.

Final Closeness Centrality code. For the final Closeness Centrality implementation we went ahead with Dijkstra’s + OpenMP approach. To get the actual closeness centrality scores we had to add code for averaging the distances that the search returned. The summation process is not parallelized since the iterations are dependent and compute bound.

Mining. Our mining script was able to get graphs of size 500-1000 vertices, depending on connections (tested on 3 accounts). Next, we pipelined it into Closeness Centrality C++ code. This was done by saving the graph in a file and then calling the C++ binary executable. We’re providing instructions with the code to let you get closeness centrality scores for people in your network. The only change needed is the authentication token, the instructions are mostly for building the code.

References

- http://www.geeksforgeeks.org/dijkstras-shortest-path-algorithm-using-priority_queue-stl/

- http://konect.uni-koblenz.de/networks/munmun_twitter_social

- https://facebook-sdk.readthedocs.io/en/latest/index.html

- http://www.boost.org/doc/libs/1_64_0/libs/graph/doc/index.html

- https://github.com/LopesManuel/MPI-Floyd-Warshall-C

- All-pairs Shortest Path Algorithm based on MPI+CUDA Distributed Parallel Programming Model

List of work by each student

Anton: Dijkstra’s implementation, final closeness centrality code, Facebook mining

Aditya: Floyd-Warshall MPI implementations and performance analysis.